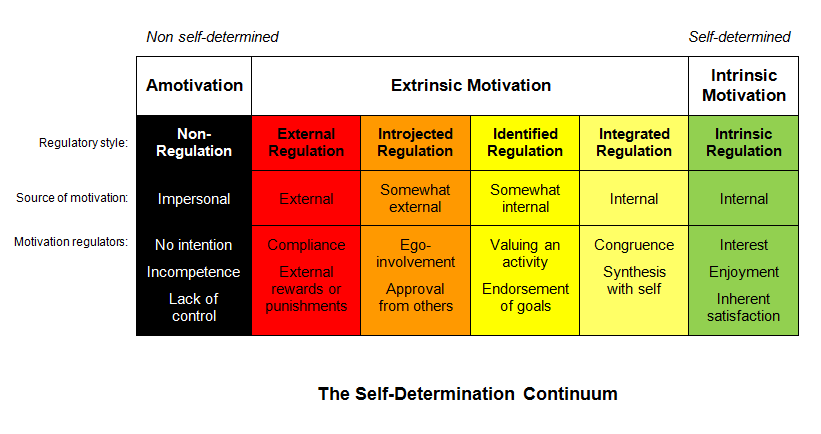

As part of my duties in conducting a Senior Research Project, I will read course texts and articles related my to project on achievement motivation and conformity. So to begin, this week I will read part of Alfie Kohn's Punished By Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive, A's, Praise, and Other Bribes. This blog will discuss the main concepts of the book so far, with some relevant examples. (This will a lengthy post since the book best explains motivation through an exposition of society and its tendencies to reward others compared to approaching the topic of motivation from a definitive angle.)

In society, the method of choice of getting anyone to do something is to provide a reward to people when they act the way we want them to. According to Kohn, "Scholars have debated this phenomenon and traced its development to the intellectual tradition known as behaviorism. The core of pop behaviorism lies in the simple eloquence of "Do this and you'll get that". We take for granted that this is the logical way to raise children, teach students, and manage employees" (p. 3).

However, Kohn takes the ambitious aim to argue that there is something profoundly wrong with this doctrine - that its assumptions are misleading and that the practices it generates are both "intrinsically objectionable and counterproductive". He states that, "To offer this indictment is not to suggest that there is anything wrong with most of the things used as rewards; the problem doesn't rest in bubble gum nor in money, love, or attention. But what's concerning is the practice of using these things as rewards. The real trouble lies when we take what people want or need and offer it on a contingent basis in order to control how they act" (p. 4). Kohn's premise is that "rewarding people for compliance is not the "the way the world works" as many insist. It is not a fundamental law of human nature. It is but one way of thinking and speaking, of organizing our experience and dealing with others. ... It actually reflects a particular ideology that can be questioned. The steep price we pay for the uncritical allegiance to the use of rewards is what makes this story not only intriguing but also deeply disconcerting" (p. 4)

Survivors of introductory psychology courses will recall that there are two major varieties of learning theory: classical conditioning (Pavlov's dogs) and operant or instrumental conditioning (Skinner's rats). Classical conditioning begins with the observation that some things produce natural responses while Operant conditioning, by contrast, is concerned with how an action is controlled. Skinner, who preferred the term reinforcement to reward, demonstrated that when a reinforcement follows a behavior, that behavior is likely to be repeated. In the end, Skinnerian theory formalizes the idea of rewards; that "Do this and you'll get that" will lead an organism to do "this " again.

Behaviorists tend to see the psychological word as scientists would see it. As a behaviorist sees humanity, humans are different than other animals only in the degree of their sophistication. To quote Watson's words on the very first page of Behaviorism, "Man is an animal different from other animals only in the types of behavior he displays". Most people like to think that the existence of uniquely human capacities would raise serious questions about reducing humans to sets of behavior. But Burrhus Fredric Skinner insisted that "organisms (including us) are nothing more than "repertoires for behaviors", and these behaviors can be fully explained by outside forces he called environmental contingencies. A person is not an originating agent; he is a locus, a point at which many genetic and environmental conditions come together in a joint effect" (p. 5-6).

Kohn argues that there are terrible consequences of patterning psychology after the natural sciences. "Psychology's subject matter is reduced to the status of the subject matter of physics and chemistry. When we try to explain things, we appeal to causes" (p. 9). Kohn believes that very notion is against how we think of humanity in our daily lives. "When most of us try to account for human behavior, though, we talk about reasons; a conscious decision rather than an automatic response to some outside force, usually plays a role" (p. 9). However, for behaviorists like Skinner, human actions are completely accounted for by external causes. Would this mean values, emotions, and ideals are mere illusions?

American thinking is largely based upon these scientific ideals. Kohn gives an anecdote from an American businessman, who said, "All that matters is the measurable outcome, and if that is judged a failure, the effort by definition was not good enough." Kohn goes on to say that, in the American mind, if something "can't be quantified, it's not real" (p. 9). He says that this thinking typifies the American mindset. "It is no accident that behaviorism is this country's major contribution to the field of psychology, or that the only philosophical movement native to the United States is pragmatism. We are a nation that prefers acting to thinking, and practice to theory; we are suspicious of intellectuals, worshipful of technology and fixated on the bottom line. We define ourselves by numbers - take-home pay and cholesterol counts, percentiles and standardized tests. By contrast, we are uneasy with intangibles and unscientific abstractions such as a sense of well-being and intrinsic motivation to learn" (p. 10)

A thorough criticism of scientism would take us too far afield. But it is important to understand that practice does rest on theory, whether or not that theory has been explicitly identified. Behind the practice of presenting a colorful dinosaur sticker to a first grader who stays silent on command is a theory that embodies distinct assumptions about the nature of knowledge, the possibility of choice, and what it means to be a human being.

Some social critics have a habit of overstating the popularity of whatever belief or practice they are keen to criticize, perhaps for dramatic effect. There is little danger of doing that here because it is hard to imagine how one could exaggerate the extent of our saturation in pop behaviorism. Regardless of political persuasion or social class, whether it be a Fortune 500 CEO or a preschool teacher, we are immersed in this doctrine; it is as American as rewarding someone with apple pie. To induce students to learn we present stickers, stars, certificates, awards, trophies, membership in elite societies, and above all grades. If the grades are good enough, some parents then hand out bicycles or cars or cash thereby offering what are, in effect, rewards for rewards. Educators are remarkably imaginative in inventing new, improved versions of the same basic idea. At one high school, for example, students were given gold ID cards if they had an A average, silver cards for a B average, and plain white cards if they didn't measure up - until objections were raised to what was widely viewed as a caste system. A full century earlier, a system developed in England for managing the behavior of school children assigned some students to monitor others and distributed tickers (redeemable for toys) to those who did what they were supposed to do. This plan, similar to what would later be called a "token economy" program of behavior modification, was adopted by the first public school in New York City in the early years of the nineteenth century. It was eventually abandoned because, in view of the school's trustees, the use of rewards "fostered a mercenary spirit" and "engendered strife and jealousies". A few years ago, some executive at the Pizza Hut restaurant chain decided - let us assume for entirely altruistic reasons - that the company should sponsor a program to encourage children to read more. The strategy for reaching this goal: bribery. For every so many books that a child reads in the "Book It!" program, the teacher provides a certificate redeemable for free pizza. But why stop with edible rewards? One representative congratulated West Georgia College for paying third graders two dollars for each book they read. "Adults are motivated by money - why not kids?" he remarked, managing to overcome the purported aversion to throwing money at problems. Politicians may quibble over how much money to spend, or whether to allow public funds to follow students to private schools, but virtually no one challenges the fundamental carrot-and-stick approach to motivation: promise educators pay raises for success or threaten their job security for failure - typically on the basis of their student's standardized test scores- and it is assumed that educational excellence will follow.

To induce children to "behave" (that is, do what we want), we rely on precisely the same theory of motivation - the only one we know - by hauling our another bag of goodies. These examples can be multiplied by the thousands, and they are not restricted to children. Any time we wish to encourage or discourage certain behaviors - getting people to lose weight or quit smoking, for instance - the method of choice is behavioral manipulation. But don't the widespread use of rewards suggest that they work? Why would a failed strategy be preferred? The answer to this will become clearer later on as its explained how and why they fail to work. For now, it will be enough to answer in temporal terms: the negative effects appear over a longer period of time, and by then their connection to the rewards may not be at all obvious. The result is that rewards keep getting used. Whacking my computer when I first turn it on may somehow help the operating system to engage, but if I had to do that every morning, I will eventually get the idea that I am not addressing the real problem. If I have to whack it harder and harder, I might even start to suspect that my quick fix is making the problem worse. Rewards don't bring about the changes we are hoping for, but the point here is also that something else is going on: The more rewards are used, the more they seem to be needed. The more often I promise you a goody to do what I want, the more I will cause you to respond to, and even to require, these goodies. More substantive reasons for you to do your best tend to evaporate, leaving you with no reason to try except for obtaining a goody. In short, the current use of rewards is due less to some fact about human nature than to the earlier us of rewards. Whether or not we are conscious that this cycle exists, it may help to explain why we have spun ourselves ever deeper in the mire of behaviorism. But aside from some troubling questions about the theory of behaviorism, what reasons do we have for disavowing this strategy? That is the question to which we now turn.

The belief that rewards will be distributed fairly, even if it takes until the next lifetime to settle accounts, is one component of what is sometimes referred to as the just "world view". The doctrine has special appeal for those who are doing well, first because it allows them to think their blessings are well-deserved, and second because it spares them from having to feel too guilty about (or take responsibility for) those who have much less. The basic idea is that people should get what they deserve, what social scientists refer to as the equity principle, seems unremarkable and, indeed, so intuitively plausible as to serve for many people virtually as a definition of fairness. Rarely do we even think to question the idea that what you put in should determine what you take out. But the value of the equity principle is not nearly as self-evident as it may seem. Once we stop to examine it, questions immediately arise as to what constitutes deservingness. Do we reward on the basis of how much effort is expended (work hard, get more goodies)? What if the result of hard work is failure? Does it make more sense then, to reward on the basis of success (do well, get more goodies)? But "do well" by whose standard? And who is responsible for the success. Excellence is often the product of cooperation and even individual achievement typically is built on the work of other people's earlier efforts. These questions lead us gradually to the recognition that equity is only one of several ways to distributed resources. Different circumstances call for different criteria. Few school principles hand out more supplies to the teachers who stayed longer the night before to finish a lesson plan; rather, they look at the size and requirements of each class. Few parents decide how much dinner to serve to each of their children on the basis of who did more for the household that day. In short, the equity model applies to only a limited range of the social encounters that are affected by the desire for justice. To assume that fairness always requires that people should get what they "earn" - that the law of the marketplace is the same things as justice - is a very dubious proposition indeed. The assumption that people should be rewarded on the basis of what they have is not as much a psychological law about human nature as it is a psychological outcome of a culture's socialization practices.

Not long ago, Kohn mentions a teacher in Missouri justify the practice of handing stickers to her young students on the grounds that the children have "earned" them. This claim struck me as an attempt to deflect attention away from - perhaps to escape responsibility for - the decision she had made to frame learning as something one does in exchange for a prize rather than intrinsically valuable. But how any stickers does a flawless spelling assignment merit? One? Ten? Why not a dollar? After the fact, one could claim that any rewards "earned" by the performance, but since these are not needed goods that must be handed out according to one one principle or another, we must eventually recognize that not only that the size of the reward is arbitrarily determined by the teacher but that the decision to give any reward reflects a theory of learning more than a theory of justice. When we repeatably promise rewards to children for acting responsibly, or to students for making an effort to learn something, or to employees for doing quality work, we are assuming that they could not or would not choose to act this way on their own. If the capacity for responsible action, the natural love of learning, and the desire to do good work are already part of who we are, then the tacit assumption to the contrary can fairly be described as dehumanizing. Now there are circumstances, especially where children are involved, in which it is difficult to imagine eliminating all vestiges of control. But anyone who is troubled by a model of human relationship founded principally on the idea of one person controlling another must ponder whether rewards are as innocuous as they are sometimes made out to be.

Clearly, punishments are harsher and more overt; there is no getting around to control in "Do this or else here's what will happen to you." But rewards simply "control through seduction rather than force." The point to be emphasized is that all rewards, by virtue of being rewards, are not attempts to influence or persuade or solve problems together but simply to control. In fact, if a task is undertaken in response to the contingency set up by the rewarder, the person's initial action in choosing the task is constrained. This feature of rewards is much easier to understand when we are being controlled than when we are doing the controlling. This is why it is so important to imagine ourselves in the other position, to take the perspective of the person whose behavior we are manipulating. It is easy for a teacher to object to a program of merit pay - to say how patronizing it is to be bribed with extra money for doing what some administrator decides is a good job. It takes much more effort for the teacher to see how the very same is true of grades or offers of extra recess when she becomes the controller. By definition, it would seem, if one person controls another, the two individuals have unequal status. The use of rewards (or punishments) is facilitated by the lack of symmetry but also acts to perpetuate it. If you doubt that rewarding someone emphasizes the rewarder's position of greater power, imagine that you have given your next-door neighbor a ride downtown, or some help moving a piece of furniture, and that he then offers you a five dollars for your trouble. If you feel insulted by that gesture, consider why this should be, what the payment implies. If rewards not only reflects differences in power but also contributes to them, it should be surprising that their use may benefit the more powerful party, the rewarder. This point would seem almost too obvious to bother mentioning except for the fact that, in practice, rewards are typically justified as being in the interests of the individual receiving them. Who benefits? - is always a useful question to ask about a deeply entrenched and widely accepted practice. In this case, it is not merely the individual rewarder who comes out ahead; it is the institution, the social practice, the status quo that is preserved by the control of people's behavior. If rewards bolster the traditional order of things, then to de-emphasize conventional rewards threatens the existing power structure.

To conclude, it is ironic that a semi-starved rat in a box, with virtually nothing to do but press on a lever for food, captures the essence of all human behavior. Also, while it may seem that reward-and-punishment strategies are inherently neutral, this is not completely true. If it were, the fact that these strategies are invariably used to promote order and obedience would have to be explained as a remarkable coincidence. Giving people rewards is not an obviously fair or appropriate practice across all situations; to the contrary, it is an inherently objectionable way of reaching our goals by virtue of its status as a means of controlling others.

(More exposition and analysis in subsequent posts!)