Resuming Alfie Kohn's Punished By Rewards, I will articulate on the negative aspects of rewards and behaviorism practices in education, and then provide alternatives to improve them. Since I am focusing on academic achievement motivation specifically in my research project, I will cover only the education-related aspects of this book rather than continue the author's analysis on the effect of rewards to parenting and work.

When kids first begin their educational journey, they are endlessly fascinated by the world. They sit rapt as the teacher reads from a storybook and once home, they excitedly tell their parents all about the new connections and facts they've learned. But by the time they have spent years within the system, their spellbound trance becomes broken. Children start complaining about homework. They count each minute until the period is over, each day until the weekend, and each week until the next break. They begin to question whether they need to know the information they're learning.

This change in attitude is usually written off as a natural development or of the loss of innocence, but instead it is the direct result of what is occurring in schools. "Though no single factor can completely account for this dismaying transformation, one feature of American education goes a long way towards explaining it: "Do this and you'll get that" (p. 143).

Two recent studies confirm what everyone already knows: rewards are constantly used in the classrooms to motivate children and improve their performance. They are offered stickers and stars, edible treats, extra recess, grades, and awards. ... When rewards don't succeed at enhancing student's interests and achievement, we offer - new rewards. When this too proves ineffective, we put the blame on the students themselves, deciding that they must lack the ability or are just too lazy to make an effort. Perhaps we sigh and reconcile ourselves to the idea that "it is not realistic to expect students to develop the motivation to learn in classrooms" (p. 143).

Setting aside everything we know about grades and motivation, Kohn states that three facts about education eventually present themselves. First, "young children don't need to be rewarded to learn". The author cites Martin Hoffman and states that "Children are disposed to try to make sense of their environments"(p. 144). Nearly every parent of a preschooler or kindergartner will attest they play with words and numbers and ideas, asking questions ceaselessly, with as purely intrinsic a motivation as can be imagined. "As children progress through elementary school, though, their approach to learning becomes increasingly extrinsic, to the point that careful observers find little evidence of student motivation to learn in a typical American classroom" (p. 144).

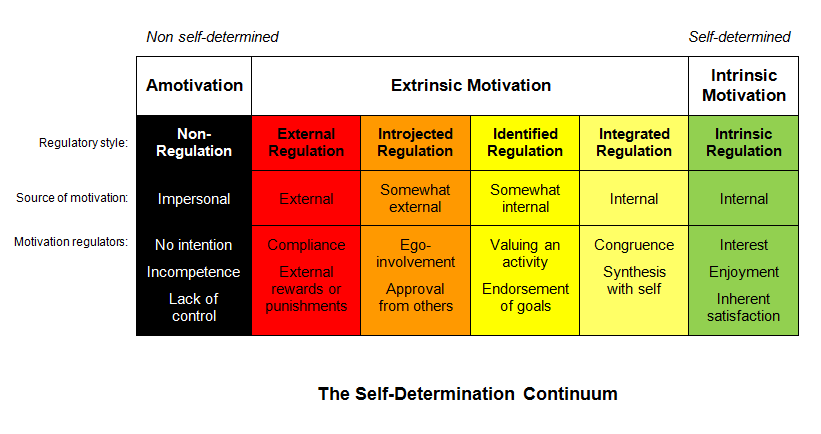

Secondly, "at any age, rewards are less effective than intrinsic motivation for promoting effective learning. The point here is quite simple; just as adults who love their work will invariably do a better job than those goaded with artificial incentives, so children are more likely to be optimal learners if they are interested in what they are learning" (p. 144). Kohn cites a study that reveals how important intrinsic motivation is for achievement. "One group of researchers tried to sort out the factors that helped third and fourth graders remember what they have been reading. They found that how interested students were in the passage was thirty times more important than how readable the passage was" (p. 145).

Taking this into consideration as well as the evidence cited in the past few blog posts, we would expect intrinsic motivation to play a prominent role in the sort of learning that involves conceptual and cognitive thinking. Kohn conjectures that educators and parents often fail to see a truth starting them in the face: "If educators are able to create the conditions under which children can become engaged with academic tasks, the acquisition of intellectual skills will follow. We want students to be rigorous thinkers, accomplished readers and writers and problem solvers who can make connections and distinctions between ideas. But the most reliable guide to a process that is promoting these things is not grades or test scores: it is the student's level of interest " (p.146). In this sense, educators and parents should be focusing their attention on who read on their own and come home chattering about what they learned that day.

Additionally, Kohn believes that interest in education is not merely a means to an end of achievement. He cites Richard Ryan, who argues that it is not enough "to conceive of the central goal of 12 years of mandatory schooling as merely a cognitive outcome" (p. 147). Instead, we should aim for children who are willing and even enthusiastic about achieving something in school, curious and excited by learning to the point of seeking out opportunities to follow their interests beyond the boundaries of school. We think school "should prepare people not just to earn a living but to live a life - a creative, humane, and sensitive life, then children's attitude towards learning are at least as important as how well they perform at any given task" (p. 147).

The third fact Kohn wanted to reiterate is that rewards for learning undermine intrinsic motivation. It is bad enough if high grades, stickers, and other Skinnerian inducements just weren't good at helping children learn. The tragedy is that they also decrease the sort of motivation that does help. Kohn references Carole Ames and Carol Dweck, two of the most penetrating thinkers on the subject of academic motivation, and states that they have "independently pointed out that we cannot explain a student's lack of interest in learning simply by citing low ability, poor performance, or low self-esteem- although these factors may play a role". According to one study, if teachers or parents emphasize the value of academic accomplishment in terms of rewards it will bring, student's interest in what they are learning will almost certainly decline.

Kohn continues in discussing two reasons for the decrease in intrinsic motivation: the controlling techniques used in the classroom and the emphasis on how well students are performing. In stating this, it must be noted, that Kohn does not argue that educators should stop providing guidance or structure to children. Rather, he says that is better to provide students with a reasonable degree of autonomy. For example, "Tests are not used so much to see what students need help with but to compel them to do the work that has been assigned" (p. 149).

Telling students what they have to do, or using extrinsic incentives to get them to do it, often contributes to the feeling of anxiety and even helplessness. Some children, as a result, relinquish their sense of autonomy. This is because "the more we try to measure, control, and pressure learning from without, the more we obstruct the tendencies of students to be actively involved and to participate in their own education. Not only does this result in a failure of students to absorb the cognitive agenda imparted by educators, but it also creates deleterious consequences for the affective agendas of schools [that is, how students are feeling]"(p.149). Kohn provides more evidence which suggests that tighter standards, additional testing, tougher grading, or more incentives will do more harm than good. Thus, the students' lack of interest becomes highly correlated with the excessive control implemented by the education system.

With regards to student performance and grades, there is an enormous difference between getting students to think about what they are doing, on the one hand, and about how well they are doing it. Students who are encouraged to think about what they are doing will likely come to find meaning in "the processes involved in the learning content, value mastery of the content itself and exhibit pride in craftsmanship" (p. 156 - from Brophy & Kher, 1986, p. 264). This is precisely what education wants to promote - partly because students who care more about the subject rather than the grade are more likely to be successful in learning it.

In contrast, "students led to think mostly about how well they are doing - or even worse, how well they are doing compared to everyone else - are less likely to do well" (p.156). Having students focus on grades and tests rather than doing well on the task or subject results in the same effect with rewards that mentioned in previous posts: they don't do as well on measures of creative thinking or conceptual learning. Even when they only have to learn things by rote, they are more apt to forget the material a week or so later. Getting people to focus on how well they are doing also increases student's fear of failure. This is harmful since "the game is not to acquire knowledge but to discover what the teacher wants, and in what form she wants it" (p.158).

For anyone who remembers my blog on Achievement goal theory, the desire to avoid failure is synonymous with children motivated by a performance avoidance goal (PAv). And the negative side to it is that PAv goals result in the least amount of learning out of the four possible goal orientations. To conclude, students often say that "getting grades is the most important thing about school". However, anything that gets children to think about their performance will undermine their interest in learning, their desire to get challenged, and ultimately the extent of their achievement.

Now that the critiques are all laid out, Kohn explains the various methods that school can undertake to gradually resolve the problems that exist in teaching and education.

The job of the educator is neither to make students motivated nor to sit passively; it is to set up the conditions that make learning possible. The challenge is not to wait until a student is interested but rather offer a stimulating environment that can be perceived by students as presenting vivid and valued options which can lead to successful learning and performance (p. 199).

Kohn argues that there should be a gradual removal of rewards existing within education, but first mentions that this is not a change that could occur overnight. For example, if a teacher chooses to stop all extrinsic motivation starting tomorrow students will not be leaping out of their seats cheering, "Hooray! Now we can be intrinsically motivated!" When teachers contemplate a new method of doing things they ought to bring the children in on the process such as by opening up a discussion with them. Secondly, even when the behaviorist tactics are abandoned, the structures and conditions necessary to facilitate appropriate motivation must also be created. Next, Kohn explains the concepts of grades by how they are justified in their use and then provides alternatives to them. The first three axioms for on the use of grades are typically justified in a classroom are as follows:

1. They make students perform better for fear of receiving a bad grade or in hope of

getting a good one.

2. They sort students on the basis of their performance which is useful for college

admission and job placement.

3. They provide feedback to students about how good a job they are doing where they

need improvement

I will tackle these in order. Kohn in 200 pages - or the equivalent of my past three blog posts - argued that the first rationale is wrong. " The carrot-and-stick approach, in general, is unsuccessful; grades, in particular, undermine intrinsic motivation and learning, which only serves to increase our reliance on them. In addressing the second justification,"Grades do serve a purpose of sorts: they enable administrators to rate and sort children, to categorize them so rigidly that they can rarely escape" (p. 201). Some critics argue that the grading categories are too rigid, the criteria too subjective, the tests on which grades are based. Thus, it is alleged that grades do not provide much useful information to business hiring or college admitting students on that basis.

Kohn argues that grades offer spurious precision since studies show greater when the work is evaluated by more than one teacher. "The trouble is not that we are sorting badly - the trouble is that we spend too much time sorting them at all. In certain circumstances, it may make sense to ascertain the skill level of each student in order to facilitate teaching or placement. But as a rule, the goal of sorting is simply not commensurate with the goal of helping students learn."(p.202) In this sense, faculties seem not to know that their chief instructional role is to promote learning, not to serve as personnel selection agents for society.

The third justification for grades is that they let students know how they are doing. In fact, informational feedback is an important part of the educational process. But if our goal is really to provide such feedback, rather than just rationalize the process of giving grades for other reasons, then reducing someone's work to a letter or number is unnecessary and terribly unhelpful.

A B+ at the top of a paper tells a student nothing about what was impressive about the paper or how it can be improved. The problem is not just that grades don't say enough about people's performance it's that the process of grading fixes their attention on their performance (p. 202).

To some degree, Kohn's criticism of grades was a true situation that I had faced in the past. In one of my Honors English courses, I had repeatedly come to my teacher because I was unsure on how to improve upon my timed essay writing. I consistently received low scores, which were indicated by a simple number on the first page of the essay. The teacher justified to the class that this was her method for grading 'holistically' and that comments would not be provided. Upon arriving at the teacher's support hours, I was given a few words of advice and was directed to look towards the essays in which I had higher grades, see what I did well, and go from there. However, this advice did not satisfy me, as I was on a downward trajectory with my writing and I wasn't going to emulate my first ever essay. The content in class got a bit more difficult over time and I needed to adapt my strategies rather than try to recycle a prior original work. I inevitably acquired a helpful tutor which restabilized my grade significantly as well as prepared for me the AP exam. But I digress.

Kohn then suggests that tests, as a form of evaluation, should be less punitive and more informative. In particular, a classroom should be an environment in which students feel safe to admit they are wrong or don't understand something so that they can ask for help.

"Ironically, grades and tests, punishments and rewards, are the enemies of safety; they therefore reduce the probability that students will speak up and that truly productive evaluation will take place" (p. 203). To summarize, grades cannot be justified on the grounds that they motivate students, because they actually undermine the sort of motivation that leads to success. Using them to sort students undercuts our efforts to educate. And to the extent we want to offer students our feedback about their performance - a goal that demands a certain amount of a caution lest their improvement in the task itself be sacrificed - there are better ways to do this than by giving grades.

The advantages cited to justify grading students to not seem terribly compelling at closer inspection. But the disadvantages only become more pronounced the more familiar one is with the research. Earlier in this post, I cited evidence showing that students who were motivated by grades or other rewards typically don't learn as well, think as deeply, care as much about what they are doing, or choose the challenge themselves at the same level as those who are not grade orientated. But the damage doesn't stop there. "Grades dilute the pleasure performance that a student experiences on successfully completing a task. They encourage cheating, strain the relationship between teacher and student, and reduce a student's sense of control over his own fate" (p. 204). Again, notice how it is not only those who are punished by F's but also those who are rewarded with A's that who bear the cost of grades.

Furthermore, Kohn outlines the gradual process by which the system of education can progress away from grading and towards the children's interest and genuine learning. His seven suggestions to teachers are as follows (pp. 208-209):

1. ...Limit the number of assignments for which you give a letter or number grade, or better yet, stop giving grades altogether. Offer substantive comments instead, in writing or in person.

2. If you feel you must give them a mark...at least limit the number of gradations. For example, switch from A/B/C/D/F to check-plus/check/check-minus.

3. Reduce the number of possible grades to two: A and Incomplete. This theory here is that any work that does not merit an A isn't finished yet. ... Most significantly, it restores proper priorities: helping students improve becomes more important than evaluating them.

4. Never grade students while they are still learning something; even more important, do not reward them for their performance at that point. Pop quizzes and the like smoother the process of coming to understand because they do not give students the time to be tentative.

5. Never grade for effort. Grades by their very nature make students less inclined to challenge themselves. Specifically, grading by a student's effort feels like an attempt to coerce them to try harder.

6. Never grade on a curve. Under no circumstances should the number of good grades be artificially limited so that one's student's success makes another's less likely. "It is not a symbol of rigor to have grades fall into a normal; distribution, rather, it is a symbol of failure - failure to teach well, failure to test well, and failure to have any influence at all on the intellectual on the intellectual lives of students" (from Milton et al, 1986, p. 285).

7. Bring students in on the evaluation process to the fullest extent. This doesn't mean let them mark off their own quizzes while the instructor reads off the answers. It means working together with them to determine the criteria by which they are learning can be assessed and having them do as much as much of the actual assessment as is practical.

The abolition of grades may upset some parents, but one reason so many seem obsessed with their children's grades and test scores is that this may be their only window into what happens at school. If you want them to accept the shift away from grades, these parents must be offered alternative sources of information about how their children are faring. Plenty of elementary schools function without grades, at least until children are ten or eleven (p. 210).

It is ambitious, but by no means impossible, to free high school students from the burden of grades. The major impediment in doing so is the fear that it would spoil student's chance of getting into college.

Given that the most selective colleges have been known to accept home-schooled children who have never set foot in a classroom, it is difficult to believe that qualified applicants would be rejected if, instead of the usual transcript, their schools sent thoughtful qualitative assessments from some of the student's teachers explaining how the school prefers to emphasize learning over sorting, tries to cultivate intrinsic motivation rather than a performance orientation, and is consequently confident that its graduates are exquisitely prepared for the rigors of college life (p. 210).

Kohn mentions as a side note that he once had the opportunity to address an entire body of students and faculty at an elite prep school.

Already, I knew, they had learned to put aside books that appealed to them so that they could prepare for the college boards. They were joining clubs that held no interest for them because they thought their membership would look good on transcripts. They were finding their friendships strained by their struggles for scarce slots at Ivy League. What some of them failed to realize is that none of this ends when they finally get to college. It starts all over again: they will scan the catalog for courses that promise easy A's, sign up for new extracurriculars to round out their resumes and react with gratitude rather than outrage when teachers when professors tell them exactly what they need to know for exams so that they can ignore the rest. Nor does this mode of existence end at college graduation. The horizon never comes closer. Now they must struggle for the next set of rewards so that they can snag the best residences, the choicest clerkships, the fast-track positions in the corporate world. Then comes the most prestigious appointments, partnerships, vice presidencies, and so on, working harder nose stuck in the future, ever more frantic. And then, well into middle age, they will wake up suddenly in the middle of the night wondering what happened to their lives. When I was finally speaking, I looked out into the audience and saw a well-dressed boy of about sixteen signaling me from the balcony. "You're telling us not to just get in a race for the traditional rewards," he said. "But what else is there?" It takes a lot to render me speechless, but I stood on that stage clutching my microphone for a few minutes and just stared. This was probably the most depressing question I have ever been asked. Here, I guessed, was a teenager who was enviably successful by conventional standards, headed by greater glories, and there was a large hole where his soul should have been. It was not a question to be answered so much as an indictment of grades, of the endless quest for rewards, or the resulting attenuation of values, that was far more scathing than any argument I could have offered." (p. 206).

Returning from the tangent, - and subsequently wrapping up this post - the available research shows that encouraging children to become fully involved with what they are working on and to stop worrying about their performance contributes to "a motivational pattern likely to promote long-term and high-quality improvement in learning" (p. 211). In this sense, students can use their mind to "discover something" rather than "learn something". The benefit of this is that children can see success and failure, not as reward and punishment, but as information. School can gradually shift their focus towards promoting intrinsic motivation by allowing for active learning, explaining the purpose of assignments so that children can value their work, eliciting curiosity, and welcoming mistakes. As for teachers' beliefs in learning, there is obviously a wide range of assumptions and practices to be found.

It is impossible to wish away the pervasiveness of Skinnerian techniques in American schools. But a recent national survey of elementary school teachers found fairly widespread understanding that rewards are not particularly effective at getting or keeping children motivated. The fact that extrinsic tactics are frequently used despite the knowledge this knowledge may reflect pressure to raise standardized test scores or keep control of a class. If teachers understand that rewards are not helpful for promoting motivation to learn, perhaps this is not the overriding goal of educators. If so, then a renewed call to emphasize the importance of motivation is what we need. We can get children hooked on learning- if that is really what we are determined to do.

And this concludes my blog series on Alfie Kohn's Punished By Rewards. Next week, I am going to begin with Conformity and Deviation by Berg and Bass.

.

.